Sandgrains, a crowdfunded documentary about overfishing in Cape Verde

Sandgrains is a crowdfunded documentary about José Fortes, a Cape Verdean migrant returning home to witness the destruction of a place he once called home. The film came about through a coincidence.

I have been making documentaries about social and environmental issues for some years, and the search for a topic on the oceans had me grasping at straws. My concern for the oceans stems from growing up on the west coast of Sweden. In younger days I would often fish for cod and crabs, which were as abundant as the fishing boats leaving port from my grandmothers village near Smögen, but in the 90s something happened. Suddenly the cod had disappeared from the coast and with it came a paralleled decline of fishing boats in the harbor. Now only two vessels remain there and they struggle to make their catch, always venturing further with each haul to make ends meet, and by the shore near my grandmother’s house I would only catch the occasional crab with not a cod in sight. Sweden had headed the same way as the Canadian Grand Banks, where cod populations had come to a complete collapse. Because of aggressive fishing policies and the ever increasing efficiency of an industrialized fishing fleet struggling to compensate for declining catches, the cod started reproducing at a much younger age to safeguard the species. This was the first sign of collapse which researchers were also detecting in Sweden only a few years later. Now the eastern Canadian fleet must go to great lengths in distant waters if they are to find any profitable fishing grounds, and the same goes for Sweden’s west coast fleet.

So how is this related to Cape Verde? I had seen a few films that dealt with the global state of the oceans, but I was looking for a personal story, because it’s often easier to connect to that, rather than listening to doomsday tales of droning researchers and panicking environmental activists. One night in 2009 I was doing odd hours at a theatre bar in my home town of Gothenburg, in Sweden, and working with me was an old friend, José Fortes. At his normal job he works with orphaned migrant children, but he stayed on at the theatre bar because of its cultural scene. By chance I was playing a borrowed CD and José instantly recognized the music as that of Tcheka, a childhood friend of his from the same village, and a prominent Cape Verdean musician. To the mournful tunes of Tcheka, José began to tell me the story of how the beach where he learned to play football as a kid had been destroyed, all because his family and their neighbors had no way of surviving now that the fish was gone. I found the story both upsetting and intriguing and decided to look into it further. José’s personal story was also compelling. He started playing football on that wide black sand beach by the fishing village RibeiradaBarca on the Cape Verdean island of Santiago, but because of the harsh environment he was adopted to an uncle in Gothenburg, Sweden, at the age of five. He never forgot the beach and kept at the football with such determination and skill that he eventually entered IFKGöteborg FC, one of Sweden’s top soccer teams and he eventually trained with Leicester FC in the UK. Because of his football career he couldn’t go back to Cape Verde for almost ten years and when he did, he found that the beach had disappeared with only rocks and mudflats left where there had once been a large expanse of black sand. All this because foreign fishing boats had taken all the fish, or so his family told him. He was so heart struck by this that he sat down to cry, and he decided to some day do something about it. This is why he told me the story.

I started studying data on local catches and also what the international fleets were up to in Cape Verde, trying to find a connection between the disappearing beach and the decline in fish stocks. A prominent expert formerly of the Swedish Fisheries Authority, MikaelCullberg, pointed out to me that the international fleets were mostly after fish like tuna, a migratory fish that passes though the Cape Verdean archipelago. He said that the local fishermen go after a much smaller coastal fish called Kavala, so that there was no conflict of interest between the international fleets and the small local wooden vessels. To get the tuna, one must venture out to open ocean and the local fishing boats couldn’t venture that far out, so all should be in good order, right? I spoke with more experts and stumbled on a book by Isabella Lövin called TystHav - ‘Silent Ocean’ in English. Mrs Lövin had been a successful environmental journalist and author as well as a member of the European Parliament for the Greens. The more I read, the more I started fearing a very near future looming without wild fish for dinner. Ever again.

JordieMontevecchi, a film maker friend and co-worker in London, was equally intrigued by the story when I spoke with him, so we decided to go for it. As we dug up more data on how Cape Verde was affected by international fisheries, we also embarked on a long and arduous journey of fundraising for the project. After nearly a year we had raised a small amount of cash from FattoriaEcologica Walden and Project Aware. Not much in film terms, but it it got me and Jordie to Cape Verde for a month in 2010; enough to shoot a trailer and do on location research.

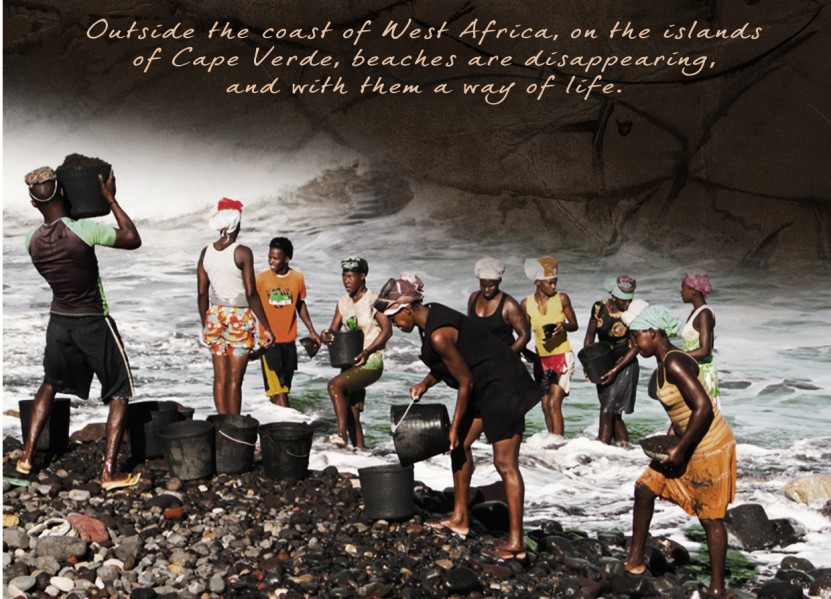

We couldn’t afford José’s ticket, unfortunately, but we were well taken care of by his extended and extensive Fortes family once in RibeiradaBarca. We stayed with his auntie, Tata, and went fishing with his cousin Nelson. We followed Já, another of José’s cousins, to the nearby beach Charco where she gathers sand each day for the survival of herself and her little son. The beach in front of the village was since long depleted of sand so now villagers are forced to go to the far end of the bay to find any. Já feared what would happen when all of it had gone, and she was acutely aware of how taking the sand affected the environment, but she had no choice if she was to feed her son. José’s auntie Tata complained that the now abandoned well outside her home had become salty as the ocean penetrated into the groundwater. The farmer behind the beach of Charco, where Já collects sand, was equally upset as his crops were failing due to the salt. To make matters worse, the mountain had started to erode into the water because the beach was no longer there protecting the shoreline, to the point that a new road had to be built after the old one was taken by the ocean. Ironically the main purpose of the road is to transport sand from Charco. So sand depletion has severe effects on the local environment, which everyone seemed both aware of and animate about, but we still lacked the link between the beach and the fish.

According to Nelson, José’s fisherman cousin, trawlers were regularly spotted fishing illegally near the coast, and this would coincide with the Kavala disappearing, but what were the trawlers doing so near the coast? First of all it’s illegal for foreign ships to fish closer to the coastline than 12 miles, and secondly they are mainly after tuna which stays further out in open waters.

We travelled to the island of Sao Vicente to find out more. There in the picturesque city of Mindelo we got to know José Ramos, a researcher, professor and nautical engineer at the University of Mindelo. He told us some worrisome stories about international fishing treaties and illegal trawling in Cape Verde. One morning we met him at a fish processing facility for an interview about the role of the EU in these treaties. He had just come back from a night-long search for a missing local fishing boat where six fishermen had perished, leaving their impoverished families fatherless. He explained that local fishermen had started to go much farther out because of the lack in Kavala fish, but that their small wooden boats were not equipped for the open ocean which led to often fatal accidents. The interview that followed dealt with how the treaties were negotiated, the lack of control and why there was a decline in fish, forcing locals to take extreme risks. Cape Verde is often covered by a brumaseca, a haze of fine dust from the Sahara, which makes aerial control of illegal trawling near impossible. The Navy makes occasional controls mainly by rubber dinghy, but they don’t always have funds to put petrol in their vessels. Ramos hinted that some foreign fleets will have up to ten identical ships but only paid permit for one, and that yet others use development incentives as a form of bribes. He spoke at some length of the corruption that seems to flourish around these treaties. The European Union however, had used subtle means to secure the access to cheap fish for its fleets. We are still investigating some of the claims he made, but one thing is clear; the EU imposed a trade embargo against Cape Verde claiming sanitary issues while in negotiations with the island nation over its only natural resource. To put things into perspective; the EU pays only between €25 (US$ 35.7) and €35 (US$ 50) per ton for something that is in the market value range of €1,400 (US$ 2004) per ton. If a vessel catches too much they only need to pay a fee of €60 (US$ 85) per ton. This way it’s profitable to fish as much as you want no matter how much you catch, or whether you get caught. Even in a callous world I figured that such a wealthy power as the EU shouldn’t need to plunder a small and arid archipelago, leaving coastal populations starving. The EU is a complex organization which helps with one hand, but can destroy with the other because of the many national and corporate interests that are involved. We had the choice of scrutinizing the other powers commercially involved in Cape Verde’s waters, but due to the opaque and inaccessible nature of fishing treaties we found it easier to look to our own politicians. Apparently the EU negotiators in 2005 were pleased with the results, and a new treaty is being ratified as I write this article.

Back in Mindelo I was still wondering why the Kavala was disappearing and what the big vessels were doing so near the coast. José’s cousin Nelson had told us of boats going close to shore at night and in days of bad visibility, and that this would coincide with several days of bad fishing. The Kavala fish has a low market value, and they stay close to the coast, so why take the risk of fishing it illegally? Apparently tuna needs live bait, particularly when fished by Long Line, a method that involves a line strung behind the boat with up to over 2500 hooks. This is also a method that generates a large bycatch which is wasted. I started thinking of how much live bait might be needed for several thousand tons of tuna and suddenly I saw a possible reason for why Nelson had to struggle so hard to feed his family. Also, the lack of fish explains why Já needs to gather sand.

We returned to Santiago and RibeiradaBarca feeling that a film somehow had to be made of this. After a visit by our associate producer Lisa Mellegård, who funded one of our cameras, we finished shooting the trailer in Cape Verde and returned to Europe, where we met up with José and started building our website, and our funding strategy. We crowdsourced Carla Guimraes as editor for the trailer and began in earnest to figure out how we would get the actual film made.

As a production model we founded Matchbox Media Collective, the world’s first multimedia cooperative with its own crowdfunding platform. We now have a fully kitted production crew on the standby until we find enough funding to go and shoot the documentary. To name but a few milestones, I met with Isabella Lövin, the Swedish MEP, for an interview in Stockholm, December 2010, and we were selected for the Sheffield Doc/Fest Crowdfunding Pitch 2011 for our innovative funding strategy, which allows for our audience to become engaged in the documentary as associate producers.

If you want to help out or get involved, visit www.sandgrains.matchboxmedia.org, and we welcome emails if you have any questions about the film topics.

Co-director of Sandgrains - A Crowdfunded Documentary